Go

back to Behaviorism Articles & Chapters

The

Three-Contingency Model of Performance Management Applied to Welfare

Reform

Richard W. Malott1

Behavior Analysis Program

Department of Psychology

Western Michigan University

Download

Word version of this article

Abstract

Rosie O’Grady and the colonel’s lady are sisters

under the skin.—Rudyard Kipling

The three-contingency model of performance management suggests contingencies

that could provide an effective basis for welfare reform. This model

also suggests an analysis of the performance-management contingencies

of traditional efforts at welfare reform; and, in turn, that analysis

suggests such traditional reform will not effectively increase functional

behavior such as job finding nor decrease dysfunctional behavior such

as drug abuse. This article is inspired by Nevin’s (1999) analysis

of welfare reform.

THE STORY

Dora’s

Deal

Dora sat fidgeting in the drab office of her case worker, Debby,

looking at the floor as Debby continued, “Now, Dora, let us

make absolutely sure you understand this; your support checks, your

food stamps, and your medical insurance will last just two years from

today. After that, no more money, no more food stamps, and no more

medical insurance. So you’ve got to get hustling, right now;

it’s no easy thing to find a job. I know two years seems like

a long time, but that time will fly. Now are you sure you understand

this?”

“Yes, ma’am, I sure do understand. But don’t you

worry none about me waitin’ no two years to find a job. I wants

a job right now. This welfare business humiliate a woman; and ever’

time I see her, my mama axe me when I gonna’ get a job. Besides,

a body can’t feed and clothe three children on what welfare

pay. I’m gonna’ start my job search first thing tomorrow”

Dora replied with grim determination.

“By the way,” Debby said, “I see you have two prior

arrests for possession of an illegal substance. You know, if you get

convicted of a drug felony while you’re receiving welfare support,

you will lose that support immediately.”

“Ma’am, don’t you worry ‘bout me none; I am

clean now.”

Debby’s

Deal

Debby sat fidgeting in the drab office of her doctoral committee

chair, Dirk , looking at the floor as Dirk continued, “Now Debby,

let us make absolutely sure you understand this; you’ve got

just two more years to finish your dissertation. Then you’ve

hit the graduate school limit, and Big State U. will drop you from

the program. So you’ve got to get hustling, right now; it’s

no easy thing to do a Ph.D. dissertation. I know two years seems like

a long time, but that time will fly. Now, are you with me?”

“Yes, Dr. Duke, I sure am. But you don’t have to worry

about me; you know I’m a self-starter. Getting my Ph.D. means

a promotion and a pay raise. And still being in school is humiliating

for a woman my age; every time I see her, my mother asks me when I’m

going to graduate. Besides, I want to send my daughter to a private

school, and I can’t do that on what Social Services pays a caseworker.

I’m going to start my literature search the first thing tomorrow,”

Debby replied, with grim determination.

Dora’s

Day

Dora’s oldest daughter grabbed the last Dunkin’ D. donut

from the box on the card table and headed off to school. Dora thought,

“Now, I’ll pick up a newspaper and checkout the classifieds,”

as she flipped on CNN. “Oh, my lord, the President did that,

and on an Easter Sunday,” she said and sat down in front of

the TV. “I’ll just watch for a couple minutes, before

I go to the newsstand.”

Two hours later, Dora arrived at the newsstand; but before she started

browsing through the boring classifieds, she’d just glance at

People Magazine. An hour later, she recalled that her two younger

children were alone, so she dropped People M. and rushed home.

Debby’s

Day

Debby’s daughter finished her granola and skimmed milk, rinsed

off the dish and spoon, and headed off to school. Debby thought, “Now,

I’ll pick up Psych. Abstracts and checkout the references,”

as she flipped on NPR. “Oh, god, the President did that and

on an Easter Sunday,” she said and sat down in front of the

FM. “I’ll just listen to NPR for a couple minutes, before

I go to the library.”

Two hours later, Debby arrived at the library, but before she started

browsing through the boring Psych. Abstracts, she’d just glance

at the APA Monitor. An hour later, she realized she’d soon be

helping support BSU’s scholarship fund, so she dropped the APA

M. and rushed out to her car, just before the officer had a chance

to ticket it. Not enough time to go back to the library now; it was

almost time for lunch and then the P.M. shift at the office.

Dora’s

Month

Dora sat fidgeting in the drab office of her case worker, looking

at the floor as Debby continued, “So, Dora, how’s the

job search going? Any hot leads? Any interviews?”

“Well, ma’am, I ain’t exactly had no interviews

yet; but I be workin’ on it,” Dora replied. “It’s

jess that it’s so hard, what with the babies and all; you know

I can’t afford no baby sitter.”

“That’s a good point,” Debby said. “And Social

Services now has a new support system where you can take your children

to our child-care facility while you look for a job.”

“Oh, that be jess the ticket, ma’am. That’ll really

help,” Dora said.

Debby’s

Month

Debby sat fidgeting in the drab office of her doctoral committee

chair, looking at the floor as Dirk continued, “So, Debby, how’s

the lit review going? Any hot leads? Any dissertation ideas?”

“Well, Dr. Duke, I don’t have any viable ideas yet; but

I’m getting close,” Debby replied. “It’s just

that it’s so hard not having my own computer to do lit searches

on the Internet so I can download the results into a data base. And

I can’t afford a computer.”

“That’s a good point,” Dirk said. “And BSU’s

Grad. College now has a new program where they will give students

interest free loans to buy computers for working on their dissertations,

especially for nontraditional students.”

“Oh, that’s wonderful, Dr. Duke. That will really help,”

Debby said.

Dora’s

Year

Dora fidgeted, as Debby continued, “Dora, it’s been a

year; and you haven’t shown any sign of progress toward getting

a job.”

Dora: “Well, it’s hard to know where to start. I . . .”

Debby: “Did you even called a single employer all year?”

Dora: “Well, ah . . .”

Debby: “I’m going to enroll you in my weekly confidence-building

support group. You’re going to learn to be assertive and cope

with your fear of failure; and we’ll also discuss how you’re

feeling about yourself.”

“Oh, that’s just the ticket, ma’am. That’ll

really help,” Dora said.

Debby’s

Year

Debby fidgeted, as Dirk continued, “Debby, it’s been

a year; and you haven’t even turned in your dissertation proposal,

let alone collected any data.”

Debby: “Well, I’ve spent a lot of time on the web looking

for . . .”

Dirk: “I haven’t even seen an outline of your proposal.”

Debby: “Well, it’s so hard with my full-time job and my

daughter; and I am a single parent; I . . .”

Dirk: “I want you to attend the Grad. College’s weekly

dissertation support group, where you’ll learn to write using

the APA Style guidelines, to design good research, and how to search

the web for research references.”

“Oh, thank God; that’s just what I need, Dr. Duke. That

will really help,” Debby said.

Dora’s

Doom

Debby: “Dora, you got arrested for possession of a controlled

substance and it looks like you’ll get convicted. And your two

years are up but still no job. I hate to say this, but you’ve

really disappointed me; and worse than that, you’re now going

to lose all social service support. I’m really sorry Dora, but

you’ve brought it all on yourself. I don’t know what’s

the problem with you people.”

Dora: “You right, ma’am. I’d don’t know what’s

wrong with me either.” Dora wiped her eyes with the back of

her hand. “I don’t know what’s gonna’ become

of me; and what they gonna’ do with my babies?”

Actually, Debby did know what was the problem with those people: “These

welfare mothers have absolutely no will power, don’t appreciation

the value of a job, can’t find their butts with a road map,

have no sense of responsibility, and no ability to delay their gratification.

What’s worse, it’s genetic; the only solution is eugenics.”

Debby’s

Doom

Dirk: “Debby, your two years are up; and not only did you not

finish your dissertation, you never even wrote a proposal. I hate

to say this, but you’ve really disappointed me; and worse than

that, you will be dismissed from our graduate program. I’m really

sorry Debby, but you’ve brought it all on yourself. I don’t

know what’s the problem with graduate students today.”

Debby: “You’re right, Dr. Duke. I don’t know what’s

wrong with me either.” Debby wiped her eyes with a tissue from

her purse. “I’ve spent so much time and money on my Ph.D.

degree; now it’s all lost, and I have to make payments on that

computer for the next four years.”

Dr.

Dirk Duke’s Doom

Dirk walked down to the faculty mailroom thinking with disgust about

Debby, “The field’s better off without a weak sister like

her who can’t find their butt with a road map. Grad students

today are just in it for a free ride. They have no sense of responsibility.

Their priorities just aren’t academic; they’re priorities

are in terms of having a good time. They aren’t real scholars;

they don’t really value a Ph.D. degree. And they can’t

delay their own personal gratification long enough to do what a scholar

needs to do. They aren’t like we were six years ago, when I

was a grad student.”

Then Dirk pulled the letter out of his mail box, opened it. It was

from Dean Bean: “Dear Dr. Dirk: I regret to inform you that

you have been denied tenure, because, during the past six years, you

failed to demonstrate sufficient scholarly productivity in terms of

the number of articles published in referred journals and in terms

of effort to achieve external funding for your research.”

What Dean Bean thought, but did not write was: “Big State U.

is better off without weaklings like this Duke character who can’t

find his butt with a road map. No sense of responsibility. Their priorities

just aren’t academic; not real scholars. Can’t delay their

personal gratification long enough to sit down and write an occasional

article. They aren’t like we were 18 years ago, when I was an

assistant professor.”

Debby’s

Deliverance

Debby sat fidgeting in the drab office of Dr. Bobby Behavior, looking

at the floor as Bobby continued, “Now here’s the deal:

I’ve talked the Department and the College into letting you

stay in our grad program, as long as you’re meeting the weekly

subgoals specified by a performance-management contract and are making

good progress on your dissertation. In addition, I’m willing

to take over Dr. Duke’s vacated position as chair of your committee,

if you’d like.”

“Oh, Dr. Behavior, I sure would appreciate that,” Debby

said.

“That’s good,” Bobby thought, “because no

one else was willing to chair your committee; but then no one else

really thinks behavior management should be applied to anyone but

the mentally handicapped and factory workers.” But what Bobby

B. said was, “We’ll break the long-range goal of completing

your dissertation into weekly subgoals. Then we’ll break the

weekly subgoals into daily subgoals. And you can e-mail me your accomplishments

once a day. Then we’ll meet once a week to review your proofs

of accomplishment and fine tune your performance-management contract

for the next week.”

“But, Dr. Behavior, I can’t even figure out a topic for

my dissertation,” Debby said.

“How about going for a two fer; how about doing your dissertation

where you work, at social services, like find some serious behavioral

problem there and use behavior analysis to solve it?” Bobby

B. said.

Dora’s

Deliverance

Debby: “Now here’s the deal: I’ve talked the Department

of Social Services into letting you continue with welfare support,

as long as you’re meeting the weekly subgoals specified by your

performance-management contract and are making good progress toward

finding a job.”

Dora: “Oh, Miz Debby, honey, I surely would appreciate that.”

Debby: “We’ll break the long-range goal of finding a job

into weekly subgoals. Then we’ll break the weekly subgoals into

daily subgoals. And you can call me about your accomplishments once

a day. And we’ll meet once a week to review your proofs of accomplishment

and fine tune your performance-management contract for the next week.”

THE

PROBLEM: NATURAL CONTINGENCIES

Traditional

Mentalistic Analyses

Why do Dora and Debby have trouble doing what it takes to find a

job or finish a dissertation? A traditional mentalistic analysis answers

this question in terms of invented inner causes, such as lack of will

power and lack of the ability to delay gratification (e.g., Dora and

Debby do not have the will power to resist the temptation of the immediate

gratification coming from People Magazine and the APA Monitor.). And

because it is hard to imagine why someone will not do something they

want to do, traditional analyses often infer a lack of appreciation

(e.g., lack of appreciation of the value of a job or a Ph.D. degree).

Many traditional explanations in terms of invented inner causes are

reifications, in that an activity (e.g., working toward a goal) is

transformed into a causal noun/thing (e.g., will power). And these

explanations are circular reifications to the extent that the proof

of the existence of that reified cause is inferred from the activity

it was invented to explain (e.g., they do not work toward their goal

because they lack will power, and you know they lack will power because

they do not work toward their goal) . (Malott, Whaley, & Malott,

p 29-30, 1997).

And why does Dora use illegal drugs? Again, a traditional mentalistic

analysis would answer in terms of circular reifications like lack

of will power and an inability to delay gratification; and if that

does not suffice an addictive personality can be reified into existence

and thrown in the pot of reification stew.

Traditional

Behavioristic Analyses

The Myth of

Incompatible Contingencies: Important Delayed vs. Trivial Immediate

Outcomes

Why do Dora and Debby have trouble doing what it takes to find a job

or finish a dissertation? A traditional behavioristic analysis answers

this question in terms similar to the mentalistic analysis, but the

“inability to delay gratification” is translated into

a “strong preference for immediate reinforcers rather than delayed

reinforcers” (e.g., the reinforcers of finding a job or getting

a Ph.D. degree are too delayed to compete with the immediate reinforcers

of scandal in the White House).

The same analysis applies to Debby’s procrastination.

And why does Dora do drugs? Again, a traditional behavioristic analysis

would answer in terms of strong control by the immediate reinforcing

effects of the drug vs. the weak control of the delayed harmful effects

of the drug.

In other words, the traditional behaviorist say this is a problem

of immediate vs. delayed outcomes. Such analyses are fortified by

extrapolations from the Skinner box where, indeed, behavior is more

readily controlled by immediate, contingent reinforcers than by 20-second-delayed

contingent reinforcers. But I will argue that such extrapolations

are overly simplified (Malott & Garcia,1991). In summary, these

traditional behavior analyses are essentially intellectualized versions

of grandmother’s common-sense analyses--"This new, me generation

just can't delay gratification like we could in the old days."

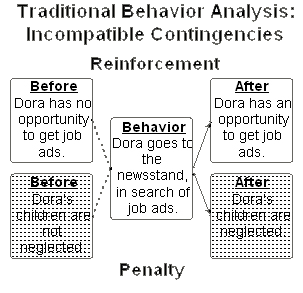

The Myth of

Incompatible Contingencies: Two Important Immediate Contingencies

A traditional behavior analysis will also point to other types of

competing contingencies. For example, traditionalists will point to

the contingencies with immediate outcomes controlling child care vs.

the contingencies with outcomes, either immediate or delayed failing,

to control the job search. (In the present example, the child-care

contingency is described in terms of a penalty contingency for searching

for job ads; this allows us to concentrate on the behavior of primary

interest, searching for job ads. The two previous pairs of diagrams

could also have been described in terms of penalizing the productive

behavior with the loss of the reinforcing opportunity to be scandalized.)

However, in these cases, the traditionalist implication is not so

much that the problem is due to the of lack of control by delayed

outcomes as much as that it is impossible to do two important, physically

incompatible things at once (e.g., search for job ads and take care

of children).

And these traditionalists will also point to the immediately aversive

punishment contingencies suppressing a computerless reference search.

I will argue that even when you remove competing contingencies, the

ineffective natural contingencies and the ineffective performance

management contingencies, will still fail to control behavior.

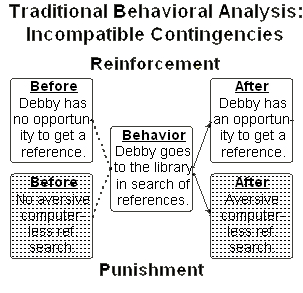

Ineffective

Traditional Interventions: Eliminating Competing Natural Contingencies

It is a common but erroneous analysis to blame competing natural contingencies

for failure of other natural contingencies to control the behavior

as we wish. True, child-care contingencies do compete with job search

contingencies. But usually when such competing contingencies are eliminated

or greatly attenuated, the natural contingencies will still fail to

maintain job-search behavior at an adequate frequency. Although there

may be an increase in the frequency of going to the newsstand to check

out the job ads, for instance, that frequency will still be too low

to produce reliable success at job finding.

And true, the aversive effort contingencies associated with going

to the library to search for references do compete with reference-search

reinforcement contingencies. But, when the purchase of the computer

eliminates or greatly attenuates such punishment contingencies, the

natural contingencies will still fail to reinforce enough reference-search

and proposal-writing behavior. The frequency of Debby’s reference

searches will still be too low to produce reliable success at completing

her dissertation. Similarly, getting rid of the TV or the FM may help,

but it will not suffice.

Ineffective

Traditional Interventions: Removing Skill Deficits

It is also true that we need skills to accomplish tasks, and sometimes

we do not have those skills. But more often, people think the problem

is skill deficit when it is really failure of natural contingencies

to support task accomplishment. Therefore, often after skill training,

the frequency of task completion does not increase greatly. And therefore,

teaching Dora how to be properly assertive may have insufficient impact

on her job-search behavior. And while this may not fit too comfortably

in the skill-deficit area, workshops to increase Dora’s self-confidence,

even if the workshops are successful, will probably have little effect

on job searching. (In fact, informal observation suggests that often

it is those who fail to achieve who are the most confident that they

can procrastinate until the last minute and will still have plenty

of time to complete the task before the deadline; and they have this

false confidence, in spite of repeated failures to start working in

time to complete tasks by their deadlines. Only those plagued with

neurotic, unrealistic fears of failure to complete the task on time,

actually start work on the task early enough to actually complete

it on time.)

Similarly, Debby’s learning to write using the APA Style guidelines,

to design good research, and to search the web for research references

does not address the problem of the natural contingencies that are

ineffective in reinforcing her working on her dissertation.

A

Radical-behavioral Analysis

The Mythical Cause of Poor Self-management

It is correct that the delay between the response and the delivery

of the reinforcer is crucial for direct-acting behavioral contingencies

such as those studied in the Skinner box. However, the problematic

contingencies of primary concern in the lives of verbal human beings

usually involve outcomes that are so delayed they are only indirect-acting

analogs to the Skinner-box contingencies; the delays are so great

that the contingencies would not control behavior even indirectly

if the person could not state a rule describing those contingencies,

that is, if the behavior were not rule-governed (Malott, Whaley, &

Malott, p 332-380, 1997). But contrary to traditional mentalistic

and behavioristic analyses, the delay is not a problem, if the person

can state a rule describing the contingency (e.g., Dora has no trouble

saving the on-sale newspaper coupons from the local supermarket, even

though she will not be able to use them until she goes to the store

two days later; and Debby will have no trouble (well, not too much

trouble) preparing and sending her dissertation-poster proposal to

the Association for Behavior Analysis, even though she will not be

able to present her poster at the conference until seven months later.)

In summary, the traditional mentalistic and traditional behavioristic

analyses illustrate the mythical cause of poor self-management--poor

self-management results from control by immediate outcomes and the

lack of control by delayed outcomes; so we fail to act in our long-run

best interests.

As the sale coupons and the poster proposal suggest, contingencies

with delayed outcomes can control the behavior of verbal people, if

the people know the rules describing those contingencies. Then why

does Dora have so much trouble getting herself to search for a job?

And why does Debby have so much trouble getting herself to search

for dissertation references and dissertation topics and so much trouble

getting herself to write her dissertation proposal? If it is not the

delayed outcomes, what is it?

The

Real Cause of Poor Self-management

Effective Natural

Contingencies.

Let us look more closely at a term we have already been using, natural

contingencies. Natural contingencies are those contingencies that

occur in nature, without special intervention, those that are not

specifically designed to control behavior. Most natural contingencies

are effective and, therefore, attract little attention. Our lives

are full of effective, natural, direct-acting Skinner-box contingencies:

When we are hungry, we eat. When we are thirsty, we drink. When we

itch, we scratch. When we are horny, we . . .

Our lives are also full of effective, natural, indirect-acting, rule-governed,

verbal analogs to Skinner-box contingencies. Even when we are not

hungry, thirsty, itchy and horny, we fill up our shopping cart with

rolled oats, Diet Coke, calamine lotion, and Sports Illustrated’s

swim-suit special, because we know the relevant establishing operations

will kick in at some time in the future.

However, often the natural contingencies are ineffective. That is

when behavior analysts are called upon, or at least should be called

upon.

Reinforceable

Response Units.

Behavioral contingencies act on reinforceable response units, like

leaving the house to go pick up a newspaper with the job notices or

leaving the house to go to the library. Behavioral contingencies act

most directly at this molecular level of reinforceable response unit,

not at the global level, like finding a job or writing a dissertation;

finding a job and writing a dissertation might take days or weeks,

or even months.

Reinforceable response units are usually single, discrete responses

of short duration, like sitting down at the computer, though they

might be long response chains, like walking from the apartment to

the newspaper stand (you could train a nonverbal organism to go to

the newsstand, pickup the paper, and return home, as long as a reinforcer

were given immediately on entering the home, and as long as there

were no long breaks in the response chain). However, the delivery

of a reinforcer at the end of the response chain would not maintain

the response unit for nonverbal organisms, if there were delays in

the chain of perhaps more than 60 seconds, as might happen if the

way to the newsstand were littered with reinforcing distractions,

such as other nonverbal organisms, especially if they were cute.

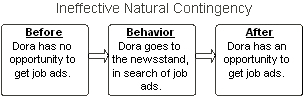

Ineffective Natural Contingencies: Dora’s Dilemma. In analyzing

ineffective natural contingencies, let us look at the reinforceable

response units, where the action is, rather than at the molar, global

response units of traditional analyses . Then we get a different perspective.

So rather than look at Dora’s finding a job, let us look at

Dora’s leaving her apartment to go to the newsstand (where she

can get a newspaper with the job notices).

The problem is that the opportunity to get the day’s classified

ad section is not a big enough reinforcer to reinforce Dora’s

leaving her apartment and going to the newsstand, regardless of the

delay in the delivery of the reinforcer (the opportunity to purchase

the newspaper). In general the outcomes contingent on each little

job-finding step are too small to reinforce those steps. They are

too small, even though those outcomes would cumulate into a very large

and reinforcing outcome, a job.

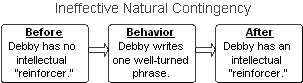

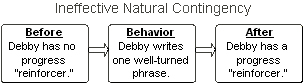

Ineffective Natural Contingencies: Debby’s Dilemma. Let us

look at a realistically small reinforceable response unit for Debby’s

writing her dissertation proposal, for example, writing a sentence,

or even more realistically, a phrase. There are two ineffective natural

contingencies for Debby’s writing. One involves the outcome

of the sight of a well-turned, logical, apt phrase—a potential

intellectual reinforcer.

The problem is that such intellectual “reinforcers” are

often to small too reinforce their production, perhaps because of

their difficulty or rarity of attainment. They are too small, even

though those outcomes would cumulate into a large and reinforcing

outcome, a well-written proposal. (These small outcomes might still

be large enough to qualify as reinforcers, in that they might reinforce

less effortful acts, like reading the well-turned phrases.)

The other ineffective natural contingency involves the outcome of

progress toward a completed dissertation and a Ph.D. degree.

The problem is that such progress “reinforcers” are also

often too small to reinforce their production. They are too small,

even though those outcomes would cumulate into a large and reinforcing

outcome, a Ph.D. degree.

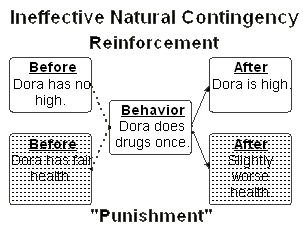

Ineffective Natural Contingencies: Dora’s Drugs. Thus

far, we have mainly considerd the problem of increasing the frequency

of helpful behavior; but in the case of consuming harmful drugs, we

must consider the problem of decreasing the frequency of harmful behavior.

Now I have argued that incompatible contingencies usually have little

effect on the frequency of helpful behavior. But, contrary to this,

without a reinforcement contingency maintaining the harmful behavior,

there would be no need to decrease the frequency of such behavior.

Without the reinforcing high, the frequency of Dora’s consuming

drugs might be zero.

The natural “punishment” contingency does not effectively

punish doing drugs becuase the outcome is too small (the outcome of

a single response is an infinitesimally small decrement in the quality

of Dora’s health). This outcome is too small, although the cumulative

outcome of hundreds of such responses might be significantly large

and very aversive.

These preceding examples illustrate one major cause of poor self-management:

Rules often fail to control behavior, if they describe contingencies

with outcomes that are too small, though of cumulative significance.

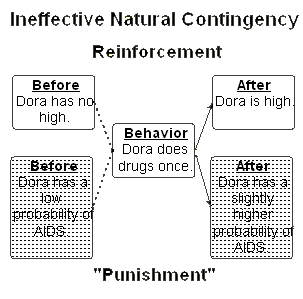

There is one other major cause of poor self-management: Rules often

fail to control behavior, if they describe contingencies with significant

but improbable outcomes. For example, Dora continues to shoot heroine

with shared needles, even though she knows she might get AIDS from

one of them. But the probability of getting AIDS from any single instance

is too small to control her behavior.

We can summarize our position as follows: Poor self-management results

from poor control by rules describing outcomes that are either too

small (though often of cumulative significance) or too improbable.

The

delay is not crucial.

Victim Blaming. We should not make the mistake of blaming the victim:

True, Dora can not get herself to find a job (she can not get her

job searching behavior under the control of the natural contingencies

so that she will succeed); but that does not mean she does not want

a job. And true, Debby can not get herself to find references (she

can not get her reference searching and her dissertation-proposal-writing

behavior under the control of the natural contingencies so that she

will succeed); but that does not mean she does not want a Ph.D. degree.

Dora and Debby care, and I hope the present analysis provides a viable

option to victim blaming, a reinforcing activity not limited to nonbehaviorists

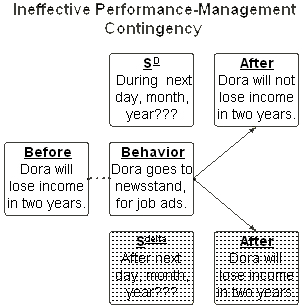

The

Solution: Performance-Management Contingencies

Traditional,

Ineffective Performance-Management Contingencies Designed to Increase

Performance

One type of ineffective performance-management contingencies, especially

legal contingencies, often places severe consequences on failure to

perform large tasks. Or more correctly, ineffective performance-management

contingencies often require the completion of a large task to avoid

a severely aversive outcome. Because of the size of the task and the

delay of the outcome to be avoided, such contingencies are usually

indirect-acting, rule-governed analogs to avoidance contingencies.

The required task is often too large to be a reinforceable response

unit, as it usually has many gaps greater than 60 seconds. For example,

Dora needs to find a job before she gets kicked off welfare. Debby

needs to complete her dissertation before she gets kicked out of grad

school. And Dirk needed to publish a horrendous number of articles

and submit a horrendous number of grant proposals before he was kicked

out of his tenure-track position. They must do those things, but it

is unclear just when they really need to get started, just when they

need to make that first reinforceable response.

To understand why these performance-management contingencies are ineffective,

we must stay at the molecular level of the reinforceable response

unit; for example, instead of Dora’s finding a job, we should

look at Dora’s leaving her apartment to pick up a newspaper.

Now there is a deadline for leaving her apartment: Dora must leave

her apartment in time to do all of the remaining tasks that will lead

to her reliably finding a job before the two years are up; otherwise,

she will have no income. But it is not clear just when that deadline

occurs.

Can she wait a day, a week, a month, or a year before she will not

have enough time left to find a job? In other words, how long will

it take her to find a job? The crucial issue is, when should she start

worrying that, if she doesn’t get moving, she won’t have

enough time to find a job before she is off welfare and in even more

horrendous financial trouble.

Deadlines in such analog avoidance contingencies are discriminative

stimuli, during which the contingency is in effect. Once the deadline

has past, the response will no longer avoid the aversive event.

According to the two-factor theory of avoidance, avoidance contingencies

control behavior, only if there is a supporting escape contingency

(Mower, 1947).

How does the before condition in these supporting escape contingencies

acquire it’s learned aversiveness? Through a verbal-analog to

pairing with the aversive outcome that the avoidance response would

avoid.

This is a verbal, rule-governed analog to a direct-acting pairing

procedure, because the paring would not be immediate (the two stimulus

conditions would not occur within 60 seconds of each other). And,

in fact, the pairing would not even have occurred before it was too

late. That is why it is a verbal, rule-governed analog. But analog

pairing can work quite well with verbal human beings. The delay between

the conditions being paired is not a problem.

Unfortunately, however, there is a problem; this pairing procedure

will not work; it will not establish as a learned aversive condition

the failure to go to the newsstand combed with proximity to the vague

deadline. Why? Because the deadline is too vague. There is no specific

time when it will be too late to avoid the loss of welfare. So there

is no specific time, whose proximity (combined with failure to go

to the newsstand) will be aversive. So there is no aversive before

condition that going to the newsstand will escape. So there is no

escape contingency that will support the avoidance response of going

to the newsstand. So Dora will lose her welfare support in two years.

Dora has too much leeway, too much opportunity for procrastination.

The same analysis applies to Debby’s procrastination and Duke’s

procrastination and most ineffective performance-management contingencies.

The problem with traditional, institutional performance-management

contingencies is that the responses specified in the contingencies

are too large (e.g., find a job), and thus the deadlines for the reinforceable

response units are too vague (e.g., sometime within the next two years.

These ineffective performance-management contingencies are little

better than the ineffective natural contingencies they were designed

to supplement.

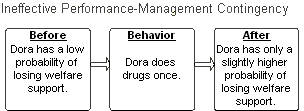

Traditional,

Ineffective Performance-Management Contingencies Designed to Decrease

Performance

The other type of ineffective performance-management contingency,

especially legal contingencies, often places severe, low probability

consequences on the occurrence of undesirable behavior. For example,

if Dora is caught using illegal drugs, she is kicked off welfare.

The problem with this, as a performance-management contingency is

that the probability of her being caught and then kicked off welfare

is too low to effectively control the frequency of her drug use.

Of course, if Dora uses illegal drugs often enough, she may likely

be caught and be kicked off welfare. But the probability that she

will be caught sooner or later exerts little control over her behavior.

It is the probability that she will be caught after the next instance

of drug use that is the major determinant of her behavior. And increasing

the severity of an improbable outcome is of little value.

Effective

Performance-Management Contingencies

Essentially all performance-management contingencies with normal,

verbal adults use instrumental outcomes, rather than hedonic outcomes.

No one will put an m&m (hedonic reinforcer) in Dora’s mouth

each time she finds a job ad nor in Debby’s mouth each time

she finds a reference. And finding one job add or finding one reference

is only an instrumental reinforcer (instrumental toward getting a

job or a Ph.D.); and such instrumental reinforcers do not seem to

be very reinforcing, in and of themselves. This distinction is important

because Dora and Debby and the rest of us need deadlines to prevent

terminal procrastination if our behavior is to be effectively controlled

by rules describing contingencies with instrumental outcomes. We do

not need deadlines when our behavior is to be controlled by rules

describing hedonic outcomes.

Furthermore, the response-unit specified in the performance contracts

needs to be much smaller than the molar response unit needed to achieve

significant outcomes (e.g., finding a job or writing a dissertation).

However, the performance-contract-specified response-unit need not

be as small as a reinforceable response unit with only minimal gaps.

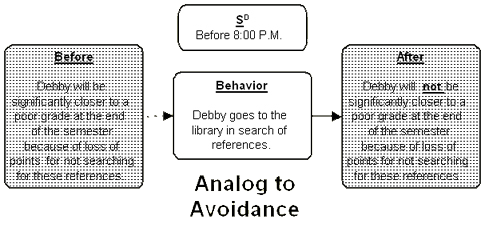

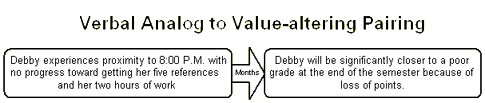

Debby’s

Deliverance, the Details

Bobby Behavior: “How about this for your first subgoals: Tomorrow,

you work at least two hours on your dissertation and e-mail me at

least five relevant references by 10:00 P.M.?

Debby: Uh huh.

Bobby B.: And for your general performance-management contract, every

time you fail to meet your hours or task sub-goals, you lose one point

from the total required for the week.

Debby: Uh huh.

Bobby B.: And if you accumulate two weeks bellow 90%, your grade for

your one-credit dissertation course goes down one letter grade.

Debby: Ouch.

Bobby B.: So you’re working with daily deadlines to avoid the

loss of points which can turn into the loss of a good grade at the

end of the semester. Will that work?”

Debby: “I sure hope so; I feel like I shouldn’t be sitting

here but should be off in search of my references right now.”

Dora’s

Deliverance, the Details

Debby: “How about this for your first subgoals: Tomorrow, you

work at least two hours on your job search and call me with at least

five relevant job ads by 10:00 P.M.?

Dora: Uh huh.

Debby: And for your general performance-management contract, every

time you fail to meet your hours or task sub-goals, you lose one point

from the total required for the week.

Dora: Uh huh.

Debby: And if you accumulate two weeks bellow 90%, you will lose one

week’s welfare support.

Dora: Ouch.

Debby: So you’re working with daily deadlines to avoid the loss

of points which can turn into the loss of support the week after your

second week of failure. Will that work?”

Dora: “Oh, my. You bet it will.”

Deliverance

Analysis

Although such performance-management contingencies effectively control

the behavior of most verbal human being, they are really only indirect-acting.

rule-governed analogs to the direct-acting avoidance contingencies

of the Skinner box. In other words, the end of the semester is too

delayed for the avoidance of the poor grade to directly support the

avoidance response. Even with verbal human beings who can state the

rule describing the indirect-acting analog contingency, there must

be direct-acting contingencies that support this rule-governed behavior.

In the present case, a direct-acting escape contingency would support

the indirect-acting rule-governed analog to avoidance.

The escape and avoidance contingencies can then combine to illustrate

the two-factor theory of avoidance. The only difference is from the

traditional application of the two-factor theory is that, in the present

case, the avoidance contingency is an indirect-acting analog rather

than a direct-acting contingency, as is needed with nonverbal animals.

(With nonverbal animals, there is a direct, contiguous pairing between

the avoided aversive condition [after condition] and the escaped warning

stimulus [before condition]. For example, in classical avoidance,

the buzzer is soon followed by an electric shock. Through this pairing,

the buzzer becomes a learned aversive warning stimulus.)

However, in Debby’s case, the pairing is too delayed for the

before condition of the escape contingency to become a learned aversive

warning stimulus simply through the pairing per se with the after

condition of the avoidance contingency. Instead, a verbal statement

describes the relation between the before condition of the escape

contingency (no progress on her thesis plus proximity to the weekly

deadline) and the after condition of the avoidance contingency (a

poor grade at the end of the semester). This statement constitutes

a verbal pairing process, analogous to the direct pairing of the buzzer

and the shock in the Skinner box. And such analog paring procedures

can be effective with verbal human beings.

These components combine in accord with the two-factor theory of

avoidance.

A similar analysis applies to the effective performance management

contingency Debby set up for Dora:

Dora’s

Drug Deal Deliverance

Debby: I’ve managed to cut a special deal with the judge and

the head of our welfare agency. You get one more chance, but we’re

going to be on you like white on rice. You’ve got to produce

a clean urine sample, everyday, seven days a week. Any time you come

within a city block of heroine, your urine sample will show it. You’ve

got to stay squeaky clean. If not, you’re permanently off welfare

and also into the Women’s Detention Center.

Dora: That’s pretty rough.

Debby: Yeah, it is; but you know it’s the best deal in town.

It’s the best I could get for you. And also, you know it’s

going to keep you off heroine.

Dora: Yeah, it’ll do that alright. And I guess it’s worth

the hassle.

This effective performance-management contingency differs from the

traditional, ineffective ones only in that the probability of the

outcome is 1.0 rather than some extremely low probability. Our behavior

is much more reliably controlled by rules describing outcomes that

are small but probable than outcomes that are large but improbable,

always keeping in mind that we are talking about the probability of

the outcome for each single instance of the response and not about

the probability, that sooner or later the outcome will occur (e.g.,

losing welfare and entering detention). In Dora’s case, the

outcome is severe, because that might be the only politically acceptable

option available to a convicted felon; but from a performance-management

perspective, the outcome could have been much less severe; and yet

the rule describing the contingency would have still controlled her

behavior.

The

Three-Contingency Model of Performance Management

The three-contingency model of performance management is a radical-behavioral

approach that takes into consideration the role of verbal behavior

(language) in the analysis of contingencies controlling and failing

to control human behavior (Malott, 1993). In the preceding diagram

of the three-contingency model of performance management applied to

drug use, we not only included the ineffective natural contingency

and the effective performance-management contingency, but also the

third contingency, the direct-acting theoretical contingency. We need

the direct-acting theoretical contingency to explain why the indirect-acting

performance-management contingency works, why it controls behavior.

In Dora’s case, much more than 60 seconds would elapse between

her injection of heroine and her arrest, loss of welfare benefits,

and incarceration. This delay of hours or days means that the aversive

outcomes of arrest, etc. would be too delayed to punish her using

heroine. So a more direct-acting contingency is needed, thus the inferred

fear of the loss of welfare and freedom (i.e., the thoughts of such

a loss) which would suppress Dora’s behavior leading to the

use of heroine so that the heroine use, itself, would not occur. Traditional,

methodological behaviorists usually object to such inferences, but

such inferences seem less an evil than trying to explain the effectiveness

of the performance management contingency by treating it simplisticly,

as if it were a direct-acting punishment contingency rather than an

indirect-acting, rule-governed analog to a punishment contingency.

We can apply the complete three-contingency model of performance management

not only to contingencies designed to reduce performance (i.e., illegal

drug use) but also to contingencies designed to increase performance.

Consider the before and after conditions of Dora’s inferred

direct-acting contingency. I describe them with summary expressions

like Dora fears losing a week’s welfare support rather than

the more cumbersome expressions like Dora experiences the aversive

condition of proximity to 8:00 P.M. with no progress toward getting

her five job ads and her two hours of work.. However, it should be

understood that the before and after conditions of this contingency

are the same the before and after conditions of the earlier escape

contingency specified in the two-factor diagram. Similarly, Debby’s

inferred direct-acting contingency in the following three-contingency

diagram, is the same as in her previous two-factor diagram.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the three-contingency model of performance management

suggests contingencies that could provide an effective basis for welfare

reform. This model also suggests an analysis of the performance-management

contingencies of traditional efforts at welfare reform; and, in turn,

that analysis suggests such traditional reform will not effectively

increase functional behavior such as job finding nor decrease dysfunctional

behavior such as drug abuse.

References

Based on Baer, D. M., Peterson, R. F., & Sherman, J. A. (1967).

Development of imitation by reinforcing behavioral similarity to a

model. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 10, 405--415.

Malott, R. W. (1993, October). The three-contingency model applied

to performance management in higher education. Educational Technology,

33, 21-28.

Malott, R. W. & Garcia, M. E. (1991). The role of private events

in rule-governed behavior. L. J. Hayes & P. Chase (Eds.), Dialogues

on verbal behavior (pp. 237-254). Reno, NV: Context Press.

Malott, R. W. , Whaley, D. W., & Malott, M. E., (1997) Elementary

principles of behavior (third edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice

Hall.

Mower, O. H. (1947). On the dual nature of learning—a reinterpretation

of “conditioning” and “problem solving.” Harvard

Educational Review, 17, 102-148.

Nevin, J. A. (1999) ??. Behavior Analysis and Social Issues. ??